Presented to the Buddha Center on Sunday, February 1, 2015.

The Great Transcendent Emancipation

Digha Nikaya 16

Forty-seven pages in length in Walshe’s translation, the Mahaparinibbana Sutta is probably the longest sutta in the Suttapitaka. Walshe calls this sutta “The Great Passing.” In a biographical context, it refers to the “passing over” or death of the Buddha. However, the translation I have given it highlights its doctrinal significance: para refers to ‘going beyond,’ much as in English, whereas a more modern translation of ‘nibbana’ than ‘extinction’ is ‘emancipation,’ since technically nibbana is the extinction of illusion (or even more technically, desirous attachment to illusion). This title could also be interpreted as referring to a realization beyond nibbana itself.

This sutta gives a meticulous account of the last year of the Buddha’s life. Two things about this sutta are of special interest: the biographical details of the Buddha’s life, of which this is the longest and most coherent account in the Pali Canon, and the doctrinal details to which the sutta refers, implicitly or explicitly. I have identified 37 of these, ranging from the statement that “Tathagatas never lie,” to the circumstances of the First Buddhist Council, held three months after the Buddha’s death.

What we will do in this talk, therefore, is divide the talk into two parts. First, we will summarize the events described in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, to provide context. This will take about 25 minutes. In the second part, we will identify and discuss the 37 principles, one by one, and in some detail. This will take approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes. Thus, the entire talk is formally 2 hours and 10 minutes. In order to process this amount of information, we will limit discussion to the end of each part and try to finish within a 2-hour window.

Part I.

The sutta opens with the Buddha staying at Vulture’s Peak near Rajagaha. We encountered Rajagaha (modern Rajgir), the first capital of the kingdom of Magadha, a kingdom that included republican communities, in the second sutta in which the Buddha is asked to explain the fruits of the homeless life. Vulture’s Peak (Gijjhakuta), literally “the hill of vultures,” Walshe describes as “a pleasant elevation above the stifling heat of Rajagaha.” It becomes famous later in the Mahayana sutras.

The king of Magadha at that time was Ajatasattu, famous for murdering his father, Bimbisara, and expanding the Magadha kingdom by conquest and expansion, so that it became the most powerful kingdom in northern India. At this time, Ajatasatru wanted to attack the Vajjians. Ajatasatru respected the Buddha, so he sent his minister, Vassakara, to use the Buddha as a kind of oracle (since, like Vulcans in the Star Trek universe, Buddhas never lie. Note the word ‘never,’ not, ‘cannot’). That is to say, a Buddha exists in a state of perfect self-synchrony, in which emancipation and the power of truth are related. We have discussed the power of truth in previous talks. Before we have seen how the dharma relates emancipation and psychic powers.

The Buddha, speaking to Ananda, presents a list of “seven principles for preventing decline” based on the law of karma. Since the Vajjians follow them, their society is healthy, strong, and able to repel any attack. Vassakara decides that to conquer the Vajjians by force is impossible, but that a war of propaganda might set them against each other. Because of this conversation, the Buddha teaches the “seven things that are conducive to welfare” to the sangha. The Buddha also gives a comprehensive discourse at Vulture’s Peak, before he moves on to Ambalatthika. In each subsequent place, he repeats the same comprehensive discourse on the mutual interdependence of morality or self-control, mindfulness or meditation, and wisdom.

We’ve encountered Ambalatthika before in the first sutta, where Suppiya and Brahmadatta are debating the merit of the Buddha within earshot of the sangha, while they were travelling together.

Afterward he travels on to Nalanda, the future site of the famous Nalanda university, but a minor village at the Buddha’s time. Here Sariputta, the disciple renowned for his wisdom, declares that there will never be anyone greater or more enlightened than Gotama. Rather than accept such lavish praise, the Buddha questions Sariputta, asking him how he could know that his statement is true?

You have spoken boldly with a bull’s voice, Sariputta, you have roared the lion’s roar of certainty! How is this? Have all the arahant Buddhas of the past appeared to you, and were the minds of all those Lords open to you, so as to say, ‘These Lords were of such virtue, such is his teaching, such his wisdom, such his way, such his liberation’ And have you perceived all the arahant Buddhas who will appear in the future … So, Sariputta, you do not have knowledge of the minds of the Buddhas of the past, the future or the present. Thus, Sariputra, have you not spoken boldly with a bull’s voice and roared the lion’s roar of certainty with your declaration.

The Buddha’s segue from praise to irony and his love of language is a characteristic idiosyncrasy of the Buddhavacana throughout the Pali Canon. I like to think that it reflects a similar quirk in the syntax of the historical Buddha. Sariputta, however, does not accept the Buddha’s criticism, saying, “Lord, the minds of the arhant Buddhas of the past, future and present are not open to me. But I know the drift of the Dhamma” (dhammanvaya). Walshe translates vaya as “way” or “drift.” The root meaning appears to be “energy, strength, vitality” (Sanskrit vayas). Also, “man, hero.” Sariputta seems to mean that he can identify a true Buddha by his behaviour. The conversation ends here. Perhaps the Buddha accepted Sariputta’s explanation, or perhaps the conclusion of the discussion has been lost.

The Buddha then goes to Pataligama. This was a small “water fort” where the Ganges, Gandhaka, and Son rivers converge. The Buddha predicts that Pataligama will become the capital. Pataliputta (Patna) became a centre of trade and commerce that attracted merchants and intellectuals. This is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world. It is also, according to the sutta, the home of thousands of spiritual beings, earth-bound sky devas (lit. ‘shining ones’) who were, interestingly, influencing the minds of the government officials telepathically! This fascinating and easily overlooked detail correlates precisely with Jacques Vallee’s study of the repeated appearance throughout history of what are today termed “UFOs,” which he considers to be both real and physical, but non-extraterrestrial. We’ll be discussing “Buddhism and the Phenomenology of the UFO” in a later talk (see Vallee, Dimensions, 2014). Of course, most academics ignore it.

The Buddha and Ananda go to Kotigama. Here the Buddha gives a talk on the Four Noble Truths.

Then they go to Nadika, where the Buddha is asked to describe the future rebirths of 12 deceased monastics and lay followers, both female and male, in terms of the grades of the path that leads to arhantship. The Buddha doesn’t like doing this, however, and he indicates that he is tired, so he teaches Ananda a special meditation called the Mirror of Dharma, by which one may attain the grade of a stream winner or, more literally, a stream entrant, at will. Perhaps the Buddha’s fatique is the first indication that something might be wrong with him.

Next, the Buddha travels to Vesali, the capital city of the Licchavi, the dominant tribe of the Vajjian Confederation, and the birthplace of Mahavira, the great Jain reformer who lived at the same time as the Buddha. The city is described as large, crowded, rich, and prosperous, with abundant food, and numerous pleasure gardens and lotus ponds. This is the residence of the royal courtesan, Amrapali, who entertains the Buddha and his entourage. Here he gives a talk on mindfulness and meditation.

Next, they visit Beluva, described as a “little village” just outside Vesali. Here the Buddha stops for the rainy season, sending the rest of the monastics back to Vesali. The Buddha wishes to spend the rainy season (July to October)[1] alone. It seems that the decision to stay in Beluva is something of a surprise, since it is clear from the sutta that the Buddha actually sent the monastics back to Vesali, rather than simply leaving them behind. Ananda stays with the Buddha.

Shortly mortal pains afflict the Buddha. By an effort of will, the Buddha overcomes these feelings and for a time seems to have recovered. Ananda comes to him and entreats the Buddha to give a final statement about the order to the sangha before he dies. Ananda’s request and the Buddha’s reply suggests there were some successional issues already developing within the order that Ananda suspect might develop into a crisis after the Buddha’s death. The Buddha seems cross:

But, Ananda, what does the order of monks expect of me? I have taught the dhamma, Ananda, making no ‘inner’ and ‘outer’: the Tathagata has no ‘teacher’s fist’ in respect of doctrines. If there is anyone who thinks, ‘I shall take charge of the order,’ or ‘The order should refer to me,’ let him make some statement about the order but the Tathagata does not think in such terms. So why should the Tathagata make a statement about the order? Ananda, I am now old, worn out, venerable, one who has traversed life’s path. I have reached the term of life, which is 80. Just as an old cart is made to go by being held together with straps, so theTathagata’s body is kept going by being strapped up. It is only when the Tathagata withdraws his attention from outward signs, and by the cessation of certain feelings, enter into the signless concentration of mind, that his body knows comfort. Therefore, Ananda, you should live as islands unto yourselves, being your own refuge, with no one else as your refuge, with the Dhamma as an island, with the dhamma as your refuge, with no other refuge.

The Buddha takes Ananda to the Capala Shrine in Vesali, where he prepares Ananda for his imminent death three months hence. Afterwards, they travel to the Gabled Hall in the Great Forest, where the Buddha calls together an assembly of the monastics and delivers a final statement to the sangha.

After the rainy season ends (October?), Ananda and the Buddha travel to Bhandagama, where he speaks on samsara and non-rebirth. The Buddha and Ananda then travel to a succession of places, including Hatthigama, Ambagama, Jambugama, and Bhogganagara, in the last of which he teaches the Four Criteria.

After this the Buddha and Ananda go to Pava (now Fazilnagar), located in the republic of Malla, north of Magahda. The Mallas are described as a brave and warlike people. Here the Buddha stays at the mango grove of Cunda the blacksmith. Cunda comes to receive teachings from the Buddha and invites him to take his morning meal with him, which he does. This meal includes a dish called ‘pig’s delight’ (sukara-maddava). The dish does not agree with the Buddha, who experiences bloody diarrhea and mortal pains.

The Buddha declares his intention to travel to Kusinara (Kushinagar), a celebrated centre of the Malla kingdom. On the road, the Buddha is overcome by fatique and rests under a tree. Overcome by thirst, he asks Ananda to bring him some water from the nearby stream. Ananda tells him that it was recently disturbed by a large number of wagons or carts, and urges the Buddha to wait till they reach the river Kakuttha. However, the Buddha cannot wait and insists that Ananda bring him the tainted water from the stream, potentially poisoning him with a toxic infection as well. The sutta naively informs us that the water became pure as Ananda approached it!

After refreshing himself, the Buddha and Ananda go on to the river Kakuttha, where the Buddha enters the river, bathes, drinks, and goes to the mango grove. There he lies down on his right side.

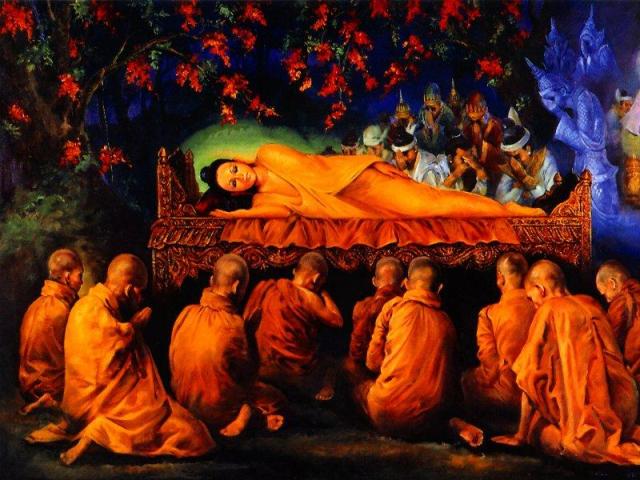

Again, the Buddha moves on, this time to the Mallas’ sal-grove near Kusinara, across the Hirannavati River, on the bank of which he lies down on his right side, his head pointing north. This is a sacred yoga posture in which righteous Hindus still prefer to die if they can arrange it. The sal trees (Shorea robusta) are barren (the sutta naively states that they burst forth into blossom!). Since the sal tree blossoms naturally in April to June (the sal tree festival is held in June), it seems likely that this occurred in the late winter, perhaps March, about the time of the Buddha’s 80th birthday. The Buddha gives final instructions concerning his funeral, the disposition of his remains and other things to Ananda, and he praises him to the monastics. As Ananda summons the Mallas to witness the death of the Buddha, the Buddha gives a dharma talk to Subhadda and ordains him, which at that time was simply a verbal formula. The Buddha then gives his final instructions to the sangha. His last words were, “Now, monks, I declare to you: all conditioned things are of a nature to decay – strive on untiringly.”

The Buddha falls into a coma, and in the third watch of the night (perhaps, 2am to 6am), he dies. Most scholars today say that this took place between 410 BCE and 370 BCE.

The Mallas honour the body of the Buddha with dance, song, music, garlands, and perfume for a whole week. Then they take the body outside the east gate to the Mallas’ shrine at Makuta-Bandhana, possibly a hall. Meanwhile, Mahakassapa has been travelling when he hears of the Buddha’s death and makes his way to Kusinara, arriving just in time to witness the cremation. The Buddha’s body is cremated and, amidst some bickering, the relics are divided into ten parts, which are distributed to various tribes who are friendly towards the Buddha and his teachings. These sites of great stupas continue to receive veneration and pilgrimage to this day. One of these relic depositories was discovered in the late 19th century by William Peppé, and is widely believed to contain at least part of the mortal remains of the Buddha.

Part II.

Almost forty fundamental spiritual principles are embedded in the narrative but are easily overlooked if one focuses on the biography.

Thus, the Mahaparinibbana Sutta constitutes one of the most important foundational documents of historical Buddhism.

First Recitation Section

Principle #1: Tathagatas Never Lie (1.2)

King Ajatasattu of Magadha uses the Buddha as an oracle because Tathagatas, having achieved self-perfection, are both internally and externally completely self-consistent, as they must be if they have reached identity with their ground in reality. This passage highlights the paradox of the coexistence of the corrupt and violent nature of n.e. India in the 5th century BCE and a deep faith in spirituality.

Principle #2: The Political Philosophy of the Buddha: Social Democracy/Anarcho-Syndicalism (1.4)

The Buddha sets out a comprehensive political philosophy, thus showing that even a transcendent being continues to care for the inhabitants of the world of samsara. Indeed, the political organization of society is a recurring theme of the Pali Canon. These principles include government by assembly, peacefulness, traditionalism, respect for seniority, women’s rights, public religion, and a national spiritual organization. These precepts follow the organizational principles of the quasi-democratic Vajjian republic, which were also similar to the principles of the Shakyan republic of the Buddha’s family.

Principle #3: Precepts for the Sangha: Communitarianism (1.6)

The precepts for the monastics also parallel those of the Vajjians, and include government by assembly, peacefulness, self-control (replacing traditionalism), respect for seniority, dispassion (replacing women’s rights), forest dwelling (replacing public religion), and mindfulness (replacing a national spiritual organization).

Principle #4: Communism (1.11)

The sangha is to be organized based on commonality of property, but does not supersede civil society, which supports the sangha so that the sangha is a function of civil acceptance, and not the reverse (therefore, the concept of a Buddhist religious government is a contradiction in terms, despite the references to a national spiritual commonality). Interestingly, the fourth continent of Sumeru, Purvavideha, which is the home of the longest-lived and most advanced race of the four races of human beings, with longevity of 1,000 years, is communistic! Presumably this will be the social system of Shambhala when, according to the Kalachakra, it appears in the 25th century of the Common Era.

Principle #5: Wisdom Is the Salvific Principle (1.12)

A recurring theme that runs through the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, almost like a refrain, is the mutual relationship between morality, ethics, virtue, or self-control; one-pointedness, concentration, or meditation; and wisdom or gnosis. This is called the threefold training or the threefold partition, and is not attributed to the Buddha, but to the nun Dhammadinna (in the Culavedalla Sutta), who the Buddha declared to be the nun foremost in wisdom. In many sects of religious Buddhism today this threefold division of the Noble Eightfold Path has virtually replaced the Noble Eightfold Path. The path is presented as beginning with the cultivation of virtue, followed by meditation. Because of these two things, wisdom, identified with enlightenment, arises automatically. The Buddha states that meditation, imbued with morality, brings great fruit and profit, and that wisdom, imbued with meditation, brings great fruit and profit, but that it is the mind imbued with wisdom that brings about emancipation. Thus, the sequence is morality (since meditation cannot be imbued with something that was does not have), meditation, and wisdom. Note, however, the subtle distinction made here between morality and meditation on the one hand and wisdom on the other. Morality and meditation are skilful means (upaya), but it is the mind-imbued wisdom that brings about emancipation. From this, we conclude that it is wisdom that is the essential salvific principle, which brings the threefold partition into alignment with the Noble Eightfold Path, the first “limb” of which is Right View or Wisdom that leads the aspirant to the attainment of the first crucial stage of the stream entrant. It seems, then, that the proper sequence of the path is wisdom, morality, meditation. Moreover, wisdom is not merely something that is attained. It is also something that is cultivated. This view is moreover confirmed in the doctrine of dependent co-origination (pattiyasamuppada), the radical or first principle of which, ignorance (avijja), is resolved by wisdom. Wisdom is also the essential attainment of a Buddha, whereas ethics and meditation, leading to the state of dispassion, is the essential attainment of an arhant. If one reads the Pali Canon in its entirely, it is clear that it is the realization of wisdom that brings about emancipation. There are many stories of aspirants attaining emancipation simply by listening to a dharma talk of the Buddha or another disciple of the Buddha, followed by a period of meditation as short as five days. Similarly, the Buddha himself says that emancipation is available after a period of meditation as short as seven days. Meditation, though essential, is not primary.

Principle #6: Sariputta and the Buddha Debate on the Greatness of the Buddha (1.16)

Sariputta, renowned for his wisdom, affirms to the Buddha that the Buddha is the best and most enlightened ascetic or Brahman, past, present, or future. Rather than accept this praise, the Buddha turns it against the Sariputta, first chidingly affirming him – “You have spoken with a bull’s voice, Sariputta, you have roared the lion’s roar of certainty” – and then questioning him – “Have all the Arhant Buddhas of the past appeared to you, and were the minds of all those Lords open to you? Have you perceived all the Arhant Buddhas who will appear in the future? Do you even know me as the Arhant Buddha?” To all of these questions Sariputta is forced to acknowledge that he did not know. Thus, the Buddha ironically concludes, “You have spoken with a bull’s voice, Sariputta; you have roared the lion’s roar of certainty.”

Such is my reading of this text, which might be read by a religious as an affirmation of Sariputta’s faith, were it not for the emphasis the Buddha placed on questioning and Sariputta’s defensive reply. Rather, the Buddha challenges Sariputta to justify his claim. Sariputta’s reputation for wisdom was not misplaced, for he turned the tables on the Buddha, and proved to the Buddha that his respect for the Buddha was not based on faith or clairvoyance, but on his knowledge of the “drift of the dharma” (dhammavaya). This recurs to the Buddha’s statement that, although we may not know the dharma, we can judge the dharma by its effect – true dharma always yields positive karma; something that has negative karma cannot be true dharma, reminiscent of the statement by Yeshua that one can judge a tree by its fruits.

One must be careful, here, of course, not to conflate real and apparent positiveness. Positiveness does not necessarily “feel good,” whereas something that does not “feel good” is not automatically negative. The Buddha has no response, thus acceding (by silence) to the wisdom of Sariputta’s reply.

Principle #7: Comprehensive Dharma versus Dharma in Brief (1.18)

If you read the Pali Canon, comprehensive dharma is often contrasted with dharma in brief or “in short” (samkhittena). As Peter Masefield, author of Divine Revelation in the Pali Canon, points out, the distinction is obscure, since the content of comprehensive dharma and dharma in brief often appears to be similar (op. cit. (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1986), pp. 101f.). Dharma in brief is frequently requested before an aspirant goes into the forest for a period of intensive solitary meditation, often culminating in arhantship. It seems like it might be similar to an oral transmission or empowerment, as in the Tantric traditions.

Principle #8: The Motif of the Axis Mundi (1.22)

The Pali Canon frequently presents the Buddha as sitting with his back against a pole or pillar. The monks sit behind the Buddha, facing the lay followers, who sit in the east facing the Buddha. Thus, to the sangha the Buddha appears in the place of the rising sun, and to the lay followers in the place of the setting sun, foremost of the sangha, with the sangha as support.

The motif of the pole or pillar is of course an allusion to the tree of awakening (the Bodhi tree, ficus religiosa), sitting under which the Buddha attained enlightenment. The Buddha also experienced his first meditative state while sitting as a child under a rose apple tree, and died between two sal trees, while lying on the ground in accordance with Indian custom. He was also born under a sal tree. Similarly, the Buddha enjoins his disciples to live in the forest as a place of refuge. India has a long history of sacred trees and forests, as well as many other societies. When the Buddha broke his vow of abstinence when he was on the verge of dying, he was seated under a tree, and Sujata, who offered him a bowl of rice gruel, believed he was the spirit of the tree to which she had come to make a food offering. The sacred tree is representative of the polar axis, like Mount Sumeru, through which communication with the higher worlds becomes possible. The pillars of Ashoka recur to this symbolism also, all of which represent the axis mundi — the cosmic axis, world axis, world pillar, columna cerului, center of the world, or world tree, the omphalos (navel) of the world, and is a universal motif of the philosophia perennis with its origins in prehistoric shamanism.

Principle #9: The Path of the Householder: The Way of Karma (1.24)

Buddhism is not merely a spirituality of monastics, ascetics, and recluses. In fact, originally the Buddha emphasized the teaching of lay people (see Hajime Nakamura, Gotama Buddha, Vol. 2). The Buddha had many disciples who were householders, and many of these disciples attained arhantship. Thus, the Buddhist science of spirituality also includes the path of the householder, which is sometimes called the lunar path or the way of the valley. The path of the householder is based primarily, but not exclusively, on the path of karma, i.e., removing negative karma through self-purification and acquiring merit through the cultivation of positive karma. Thus, Buddhism is not divorced from practical life, and reveals itself to be a pragmatic spiritual philosophy. This is shown by the Buddha’s summary of the perils and advantages of good and bad morality, which he designates failure and success in morality. The advantages of success in good morality, i.e., good karma, include wealth, reputation, confidence and assurance, dying unconfused, and rebirth in a higher world. It is clear from this and other passages that although the sangha was organized in a communitarian and, indeed, communistic way, the Buddha realized that the extension of that system of social organization to civil society as a whole was not practical. It does not seem that the Buddha opposed property and wealth in civil society, for example, though it is clear from other passages that he saw wealth as imposing special social obligations on the wealthy, and that he advocated social redistribution of property and wealth for the general good. It is, however, clear that the Buddha saw the development of money and property as socially pernicious factors that lead to criminality, violence, and war.

Principle #10: The Cohabitation of Devas and People (1.26)

The word “deva” is usually translated as “god,” but this is really a very unsatisfactory translation. The English word means “that which is called or invoked,” whereas the Sanskrit/Pali word means “shining,” referring to a celestial being of light, rather like Plato’s bisexual flying spheres. According to the PED, devas are splendid, mobile, beautiful, good, and luminous, as well as continuous with the life of humanity and all beings. They are beings who occupy higher worlds in the system of vertical extension that defines samsara, but it is clear from this passage that some devas also coexist with humanity. These earthbound devas are described as minor devas. These include ugly dwarfs (kumbhandas), aerial spirits connected with trees and flowers that dwell in the scents of bark, sap, and blossom (gandharvas), great snakes that can take human form and live in streams, oceans, and caves (nagas), nature fairies associated with woods and mountains, who also appear as ghosts that inhabits wilderness areas and threaten travellers (yakshas), and finally large humanoid birds (garudas). Interestingly, Patna is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places on earth and the largest city in the world between 300 and 195 BCE. About 300 BCE, a hundred years after the death of the Buddha, its population was 400,000. As one can see from the text, thousands of devas invisibly inhabited this city, influencing the minds of the inhabitants telepathically.

Principle #11: The Divine Eye: Ajna Cakra (1.27)

The “divine eye” (dibba-cakkhu) is referred to frequently throughout the Pali Canon. In the Pali Canon, this is one of the six gnoses (chalabhiññā). In this context, it refers to knowing the karmic destinations of others. However, it has a larger meaning as well. It is enumerated as one of the three wisdoms (tevijja or tivijja), along with remembering past lives and extinction of mental intoxicants. In the Maha-Saccaka Sutta, the Buddha says he obtained the divine eye during the second watch of the night (10pm-2am) of his enlightenment. In the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, it is by means of the divine eye that the Buddha sees devas. The divine eye is also a universal symbolic motif or archetype. In Egyptian mythology, one finds the eye of Horus. It also appears in Freemasonry, where a semi-circular glory appears below the eye, which is enclosed in a triangle. In Christianity, it represents the Eye of Providence, where clouds or sunbursts surround it. The Eye of Providence also appears on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of the French Revolution.

In the Indian chakra system, the eye appears as the ajna chakra, the eye of intuition and intellect, located in the centre of the forehead. In Tibetan Buddhism, the “third eye” is the upper end of the central energy channel that runs up through the spine to the top of the head. This centre is also important in Qigong, Sufism, and Cabala. In human beings, the divine eye corresponds to the pineal gland, in the centre of the brain, a vestigial third eye that actually appears in lizards, amphibians, and fish. Descartes called this organ “the seat of the soul.” Modern research has discovered that the pineal gland is the source of naturally occurring dimethyltryptamine (DMT), the most powerful psychedelic known, which is also widely found throughout nature. Interestingly, DMT facilitates vivid otherworldly visions including encounters with non-human entities of exactly the sort we have been describing.

Principle #12: The Buddha Was Not an Extreme Ascetic (1.30)

Although it is well-known that the Buddha rejected the extreme asceticism of the proto-Shaivite samanas with whom he associated prior to his enlightenment, the Buddha is still regarded as moderately ascetic, illustrated for example by the quite rigid rules of the Vinaya. Nevertheless, it is clear from the Pali Canon that the Buddha’s life, while simple, also had its pleasures. There are numerous examples in the Pali Canon in which the Buddha and his entourage are invited to the home of a wealthy local person, usually either political figures or celebrities, to be entertained with a fine meal of choice hard and soft food, which they invariably ate to their satisfaction. Since the Buddha travelled extensively, this must have occurred fairly frequently. The Buddha and his entourage also often occupied fairly comfortable parks and other places of great natural beauty. These facts stand as a useful corrective to the one-sided view that the Buddha was exclusively ascetic.

Principle #13: A Meaningful Miracle: More Evidence of Proto-Tantra (1.33)

Although the Pali Canon is largely naturalistic in its descriptions of people and events, it does attest to the reality of psychic powers, and sometimes these appear as full-blown miracles, as in the story of the Buddha and his entourage teleporting themselves from one side of the Ganges to the other. This is especially ironic in view of the disparagement of miracles by the Buddha in About Patikaputta (Patikaputta Sutta, 1.4). Similarly, Yeshua disparages those who seek for a sign, declaring that no sign will be given to them, yet the Gospels and the Church ascribe miracles to him as the proof of his divinity.

The Buddha clearly saw that the belief in miracles leads to a superstitious reverence for the person rather than the one true miracle, the miracle of the dharma itself, which leads to emancipation. Therefore, I believe we can reliably state that the Buddha did not perform miracles for display and that these stories are later inventions. Nevertheless, the presence of miracles of this type in the Pali Canon is another indication of the early development of proto-Tantric literary motifs even in the first period of pre-sectarian Buddhism, much as Gnosticism appeared early in the development of the Christian tradition. One can, of course, derive valid teachings from such stories even if they are not literally or historically true.

Second Recitation Section

Principle #14: The Mirror of Dharma (2.8)

The Mirror of Dharma presents a method whereby the aspirants can realize for themselves the state of stream entry, whereby they realize the fact that they will achieve emancipation within no more than seven lives. The method is to cultivate absolute confidence in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. This method must be differentiated form Christian faith, however, which is virtually defined as belief not based on proof, whereas the Buddha states that the “unwavering confidence” to which he refers is based on “inspection, leading onward, to be comprehended by the wise each one for himself.” Moreover, the morality of such an aspirant must be perfect. By this method, one can know for oneself as a matter of certainty that one has achieved stream-entry.

Principle #15: Mindfulness (2.12, 2.13)

The Pali word translated as “mindfulness” is sati. According to the PED, the etymological meaning of this word is “memory, to remember,” also: “recognition, consciousness, intentness of mind, wakefulness of mind, mindfulness, alertness, lucidity of mind, self-possession, conscience, self-consciousness.” The Sanskrit word is smrti, which also refers to the oral recitation tradition of the Vedas. The reference to self-consciousness is somewhat disconcerting, given the Buddha’s rejection of the atta (atman) theory, commonly identified with the self. Mindfulness is probably also connected with the recollection of past lives, which is strongly emphasized throughout the Pali Canon. Mindfulness begins with mindfulness of the body, and is then extended to feelings, mind, and mind-objects.

Principle #16: A Courtesan Entertains the Buddha (2.14)

As we have seen, although the Buddha clearly lived a very modest and simple life, it was not without its luxuries, in the form of the choicest hard and soft food when prominent people in various communities entertained him and his close circle of monastics. It is also clear that the Buddha interacted with and taught women without distinction. A striking confirmation of both of these observations is the Buddha’s interaction with Ambapali, a wealthy ganika who lived in the Licchavi city of Vesali, part of the Vajjian confederacy. Although Walshe renders the Pali word ganika by “courtesan,” comparing her to the Japanese tradition of the geisha, the PED simply renders the word as “harlot,” “one who belongs to the crowd,” i.e., a common woman or, perhaps, a promiscuous woman. Nonetheless, Ambapali was a wealthy and beautiful woman who was a nagavradu, a royal courtesan who was also a prominent citizen of the town.

The Buddha stayed in her mango grove, taught her the dharma, and went to her home for his morning meal, accompanied by his monastics. So much for the Vinaya rule against consorting with women, and a prostitute at that! Clearly, the Buddha was neither a fundamentalist nor a judgmental prude. He consorted with women, taught them the dharma on an equal basis with men, and was not above enjoying a fine meal or the company of a beautiful, albeit high class, prostitute. In this and in many other ways, the Buddha appears similar to Yeshua (Jesus). Ambapali made a gift of her mango grove to the sangha, which the Buddha accepted.

Principle #17: Energy, the Force of Life, Health, and Longevity (2.23)

Here we encounter the first major sign of the Buddha’s impending illness, characterized by diarrhea and sharp pains so severe as to suggest dying, about ten months before his death. The monastics remained at Ambapali’s park in Vesali, whereas the Buddha spent his last rainy season (July–September) in Beluva, a small town outside the southern gate of Vesali. What is most interesting about this passage, however, is the reference to energy and a “force of life” by which the Buddha was able to overcome his illness and postpone its effects so that he could take his leave of the order of monastics. The Buddha recommends the cultivation of energy throughout the Pali Canon, but only in a few places is it clear that this energy is an iddhi, a psychic power that has intrinsically healing and life-giving effects, comparable in fact to kundalini, which the Buddha appears to have experienced during his ascetic period. This brings the Buddha’s teachings into relation with kundalini yoga, the Tibetan concept of tumo, the Chinese concept of qi, etc.

Principle #18: Inner and Outer Dharma (2.25)

Here and elsewhere the Buddha indicates that his teaching has no “inner” and “outer,” that he has no “teacher’s fist” in respect of doctrines. This is widely interpreted to mean that Buddhism is exoteric, and that there is no esoteric dharma, no “secret wisdom,” such as Vajrayana, Tantra, Theosophy, etc. imply. However, this is not, strictly speaking, what the Buddha says. The Buddha says that he makes no distinction between inner and outer, teaching everything to everyone openly and without secrecy. Walshe himself recognizes this when he states that there is no contradiction here between this passage and the Simsapa Sutta. In the latter, the Buddha distinguishes between knowledge that leads to liberation and other forms of knowledge, “vast as the leaves in the simsapa forest.” The latter is of the same order as the former, and is realized because of realization. “Even so, bhikshus, much more is the direct knowledge that I have known, but that has not been taught. Few is that which has been taught.” The distinction that the Buddha is making appears to be between praxis and gnosis, the latter the goal of the former. Thus, the latter does in effect constitute a secret wisdom, an untaught knowledge that is nonetheless the object of realization. What the Buddha is actually saying here is that he openly teaches the entirety of wisdom, but that he emphasizes the praxis first, because it is through the latter that one realizes the former. In the Simsapa Sutta, the praxis referred to is the Four Noble Truths. Clearly, however, the Buddha taught a great deal more than the Four Noble Truths. This is the only interpretation that reconciles and harmonizes all relevant passages, and shows the importance of not selecting the passages that one likes, but rather referring to and collating all relevant passages in order to arrive at a synthetic interpretation.

Principle #19: The Sangha Has No Leader (2.25)

In this very significant passage, the Buddha makes it clear that he does not want to be succeeded as head of the sangha. In other passages the Buddha disdains being thought of as a “leader,” referring to himself rather as a friend amongst friends. Later in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, the Buddha states that the monastics should take the dharma as their leader. Nevertheless, after the Buddha’s death the sangha appointed Mahakassapa, at his own instigation, as its leader at the First Buddhist Council, followed by Ananda. Since the appointment of a leader violates the Buddha’s dictum with respect to the organization of the sangha, one may question the legitimacy of the early Buddhist councils, and in fact, their legitimacy did become an issue when the Mahasamghikas – the majority – and the Sthaviras – precursors of the Theravada – split following the Second Buddhist Council over questions concerning the rules of the Vinaya and the infallibility of the arhants. This split became the basis of the division into the Hinayana and the Mahayana.

Principle #20: The Dharma Is the Only Refuge (2.26)

The monastics are to live freely as individuals, within a cooperative sangha, with themselves and the dharma as their only refuge (sometimes translated as “retreat”). Again, the reliance on the self is paradoxical in light of the anatta doctrine. Some scholars believe that the formula of the Triple Jewel, i.e., taking refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha is a later innovation that arose about the time of Ashoka (3rd cent. BCE), and that the original refuge formula referred to the Dharma only. Clearly, the kind of sangha described by the Buddha is very different from the hierarchical, authoritarian sangha that we often see today. Although the Buddha did substitute respect for seniority for egalitarianism after his death, the sangha is still supposed to emphasize independent self-inquiry and free thought and consensus (failing which, majority rule), without excessive attachment to rules, rituals, or beliefs and without a singular leader. Recently, the Dalai Lama, to his credit, has honoured the Buddha’s dictum by stepping down as political leader of the Tibetan Administration in Exile and fostering a democratic constitution. In this regard, the Buddha appears to be exceptionally modern.

Third Recitation Section

Principle #21: The Four Roads to Power (3.3)

The Four Roads to Power are another example of magical or proto-Tantric thinking in the Pali Canon. This practice is not aimed only at awakening or enlightenment but also the development of psychic powers, in this context, longevity. In Walshe’s translation, success in this practice would enable the practitioner to live for a hundred years, close to the maximum longevity of a human being. Specifically, had Ananda taken the hint, he might have asked the Buddha to extend his life by this means and live another 20 years. However, Ananda – who is represented in the suttas as a bit of a dullard – did not take the hint.

The four roads to power (iddhipada) are not explained further in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, but we know what was involved from Viraddha Sutta (SN 51.2). In this sutta, the Buddha states that the practice consists of the development of four qualities: will (chanda), energy (viriya), intention (citta), and investigation (vimamsa), which are in turn based on the cultivation of concentration (samadhi) and concentrated mental aspiration (padhana-sankhara).

Principle #22: The Dharma, the Power of Truth, and Merit (3.7)

We see again a reference in the “dhamma of wondrous effect” to the universal idea that pervades the Pali Canon, especially the Jatakas, of the power of truth or the act of truth. This is a pan-Indian idea that we have discussed before, in which the ultimate truth of things itself exercises an influence that is beneficial and powerful. Mahatma Gandhi utilized the power of truth as a political principle, which he called satyagraha. This is also the principle by which merit may be acquired. The study, teaching, or recitation of dharma is itself held to be intrinsically efficacious and beneficial.

Principle #23: Conscious Dying (3.10)

According to this passage, the Buddha did not die as a matter of accident or involuntarily, he deliberately renounced the life principle, mindfully and with full awareness. One might be inclined to regard this as mythologization, but one would be mistaken. This principle of conscious dying is also found amongst the Tibetan lamas, some of whom are reputedly able to will themselves to death intentionally. This is widely attested. This practice is portrayed in the movie, Little Buddha (1993). In Tibetan Buddhism, this practice is called phowa. It is the highest of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Dzogchen meditation is considered the highest and greatest phowa practice.

Principle #24: Two Nirvanas: With and Without Remainder (3.20)

Those who attended my series of talks on the Pali Canon last year will remember that there is not one but two types of nirvana, the final “blowing out” or extinction of desirous attachment: one with and one without “remainder.” The arhant who attains nirvana ceases to make new karma due to the absence of desirous attachment, but existing karma still needs to work itself out. This suggests that karma is not destroyed by nirvana. If all karma were destroyed by nirvana, then one would die immediately. If the destruction of karma were the precondition of attaining nirvana, then, the attainment of nirvana would be impossible. The Buddha does appear to teach that the attainment of nirvana destroys much karma, but not all. This point requires further research. This view of nirvana also corresponds to the Buddha’s life. After he attained enlightenment, the Buddha remained in an altered state of consciousness for a whole week, after which he returned to normal consciousness. He continued to live, and the evidence of the Pali Canon is that he continued to engage in spiritual retreats, practising mindfulness of the breath – this behaviour makes no sense if the Buddha were already a perfected being, does it? Rather, it implies a being who still needs and benefits from spiritual practice. Finally, the Buddha exhausted his remaining karma and renounced the last vestige of attachment to life. He died, attaining the state of perfection called parinibbana, “final emancipation,” characterized by absolute transcendence.

Principle #25: Eight Liberations: The Eight Jhanas (3.33)

- Rapture and happiness born of seclusion.

- Delight and happiness born of concentration without applied or sustained thought.

- Quiet, subtle and pervasive happiness, subtle enjoyment of mindful and equanimous mind, without rapture.

- Stability, stillness, and equanimity, without happiness.

- Infinite space.

- Infinite consciousness.

- Nothing.

- Neither perception nor non-perception – opening to the transdual.

Cessation of Feeling and Perception (this level is not attested in all sources)

Principle #26: The Buddha’s Enlightenment Experience (3.34)

Here we have a succinct statement of the Buddha’s monumental enlightenment experience, the reference to having just attained supreme enlightenment. This appears to be an early statement, there being no reference to the three watches of the night, consisting of the recollection of past lives, karma, and dependent co-origination (pattiyasamuppada), respectively. At sunrise, he attains full enlightenment, characterized by the encounter with Mara and the cessation of desirous attachment. Here, however, the Buddha simply attains supreme enlightenment in a moment, suggesting the instantaneous theory of liberation. Here we learn the name of the place, Uruvela, located in the state of Bihar; the river – Neranjara –and the tree – the Goatherd’s Banyan tree. Goat herders, having gone to the shade of the Banyan tree, would sit there, hence the name. Interestingly, the commentaries claim that this tree was located to the east of the “awakening tree,” whereas the sutta seems to suggest that this was the “awakening tree.”

Principle #27: Energy, the Force of Life, Health, and Longevity (3.40)

What is most interesting about this passage is the reference to energy and a “force of life” by which the Buddha was able to overcome his illness and postpone its effects so that he could take his leave of the order of monastics. The Buddha recommends the cultivation of energy throughout the Pali Canon, but only in a few places is it clear that this energy is an iddhi, a psychic power that has intrinsically healing and life-giving effects, comparable in fact to kundalini, which the Buddha appears to have experienced during his ascetic period. This brings the Buddha’s teachings into relation with kundalini yoga, the Tibetan concept of tumo, the Chinese concept of qi, etc. and is indicative of an authentic science of enlightenment (see Principle #17).

Principle #28: The Intercourse of Devas and People (3.50)

This passage is interesting because it implies several things. First, that the Buddha’s dharma is not directed at humans only, but that it is also directed at spiritual beings (devas). We have already alluded to this principle (see Principle #10).

Fourth Recitation Section

Principle #29: The Criteria of Authentic Dharma (4.8)

After the death of the Buddha, the Buddha’s sermons were remembered and recited by the sangha, especially by Ananda, who had been the Buddha’s personal attendant for the last 25 years of his life. Since only Buddhist arhants were permitted to participate in the First Buddhist Council, we are fortunate that Ananda, rather conveniently it seems, attained arhantship on the night before the council met, since without his participation many of the Buddha’s teachings would have been lost. Thenceforth, the sangha would come together to rehearse the teachings of the Buddha based on the memories of the participants. Of course, as the participants died off, the nature of this transmission changed. From being memories of the actual hearers, the recollections increasingly focused on questions of doctrine, clarification, and codification. These traditions were handed down in this way for almost 300 years. With the passage of time, it became increasingly important to verify the validity of these teachings.

It is therefore of interest to read in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta the criteria that were applied to verify the validity of the teachings that were passed down. The sutta identifies four primary sources of such teachings that may be considered: the Buddha himself, but also the community of elders and teachers; a group of many elders; and a single elder. The difference between the community of elders and a group of many elders is not clear, but the sources of authority are clearly the Buddha himself and the senior bhikkus or theras, both as individuals and in concert with others. According to the PED, any bhikku of any seniority may be called “thera” because of his wisdom, and in fact, the Mahaparinibbana Sutta says that any monk may claim to have heard a teaching from “the Lord’s own lips.”

So much for the admissible sources of teachings. The Buddha then cautions that any such claim is neither to be approved nor disapproved. Rather, “his words and expressions should be carefully noted and compared with the Suttas and reviewed in the light of the discipline [Vinaya].” If the teaching conforms to the Suttas or the discipline, it is to be accepted. If it does not conform, it is to be rejected. Thus, a continuous preservation of established tradition is guaranteed. The Buddha does not say who is sanctioned to verify the teachings. However, elsewhere he says that decisions are to be made by consensus of the sangha, or, failing consensus, by majority rule.

An important point to note in this validation procedure is that it is ideological, not historical. The primary criterion is not whether the words and circumstances of the teaching are historically accurate or not, but whether they conform to the established truth of the dharma based on previously accepted teachings. In other words, is there a reasonable continuity of teaching? Receiving a teaching from the Lord’s own lips is the first criterion, but not the only one. Thus, the accusation that is frequently made against the Mahayana sutras that they are false because they are non-historical is proved irrelevant. The truth or falsity of the Mahayana sutras is to be validated based on the same criteria as the Pali suttas themselves, i.e., do they conform with the established teachings of the Buddha as handed down by tradition? In this context, therefore, do they conform to the Pali suttas, which are doubtless older than all but the oldest Mahayana sutras (circa first century BCE). In the same way, the conformity of the Pali texts with each other must also be subject to the same scrutiny.

Principle #30: The Buddha’s Last Meal: Not Food Poisoning (4.18)

The Buddha’s final meal is translated by Maurice Walshe as “pig’s delight,” thus glossing over the obscurity of the Pali phrase, sukara-maddava, which may refer to pork or a kind of truffle. This story has led to the speculation that the Buddha died of food poisoning. However, Dr. Mettanando Bhikkhu, in his article, “How the Buddha Died” (2001, May 15 –http://www.budsas.org/ebud/ebdha192.htm), suggests that food poisoning is an unlikely explanation of the Buddha’s sickness, first, because the Buddha felt the onset of the sickness very quickly, whereas food poisoning takes several hours to incubate, and second, because food poisoning does not cause the bloody diarrhea described in the sutta. He also rejects chemical poisoning, peptic ulcer, and haemorrhoids. Dr. Mettanando’s conclusion, based on the medical information provided in the suttas, is that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a medical condition in which inflammation and injury of the small intestine result from inadequate blood supply – a common disease of the elderly that is lethal after ten to twenty hours. Thus, it was not the final meal that killed the Buddha, but old age, although the size of the meal that the Buddha consumed may have been the trigger that brought about the second and final episode of the disease that we know from previous passages had begun to afflict the Buddha some ten months’ before. The cogency of Dr. Mettanando’s analysis also gives us confidence in the historical accuracy of the Mahaparinibbana Sutta.

Fifth Recitation Section

Principle #31: Women (5.9)

Hearers of my talk, “The Status of Women in Ancient India and the Pali Tradition,” will be aware that there are two distinct attitudes towards women expressed in the Pali Canon. One attitude disparages women, grudgingly admits that women are capable of enlightenment, and admits women to the sangha as “second-class citizens,” whereas the other makes no distinction of any kind between men and women, and admits women to the sangha, apparently on an equal basis to men. As we have seen in our discussion of the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, the Buddha was not above enjoying a fine meal with a courtesan. Here, however, we see another, quite incompatible attitude towards women: we should not look at them, we should not speak to them, and if they speak to us, we should be very careful. The Buddha, of course, did speak to Ambapali. He delivered a talk on the dharma to her, which (the text states) instructed, inspired, fired, and delighted her. Of course, it is possible that the rest of his entourage remained discreetly silent throughout the meal. Perhaps. On the other hand, perhaps what we are seeing here is two opposed views of women that are mutually incompatible, as Bhikkhu Bodhi has suggested in his introduction to the Anguttara Nikaya. If we accept Bodhi’s view, then we must either believe that the Buddha held two incompatible views simultaneously; that he abandoned one view in favour of the other at some point in his career – perhaps when Ananda “convinced” him to allow women to be admitted to the sangha; or that one of these views is an imposition by anonymous misogynistic monastic redactors of the Pali Canon. Hearers of my talk will know that my view, which I consider the common sense one, is the last one, since the first two views imply that the Buddha was unenlightened.

Principle #32: Ananda (5.13)

It is ironic that Ananda, who was called the Guardian of the Dharma due to his photographic memory, was both the Buddha’s closest disciple and the least accomplished. In many ways, he is portrayed in the suttas as being a bit thick. Nevertheless, he served the Buddha faithfully as his personal attendant during the final 25 years of the Buddha’s ministry, when the Buddha was 55 to 80 years old, and became the source of much of the sutta tradition collected in the Pali Canon. Ananda and the Buddha were first cousins through their father, King Suddhodhana. The Buddha described him as kind, unselfish, popular, and thoughtful, as well as chief in conduct, service, and memory. Nevertheless, Ananda’s participation in the First Buddhist Council, convened by Mahakassapa, the Buddha’s disciple who was foremost in asceticism, was contested because he was only a stream entrant. The Pali Canon portrays Ananda as an imperfect, albeit sympathetic, figure, lonely and isolated following the death of the Buddha. Nevertheless, he rather conveniently attains nirvana on the eve prior to the convention of the First Buddhist Council, during which he was severely criticized by the arhants for persuading the Buddha to ordain women, as well as his failure to ascertain from the Buddha which were the major and which were the minor rules of the Vinaya.

Principle #33: The Gradual Versus the Instantaneous Path (5.27)

The reference to four grades of attainment recalls the discussion that one finds in various places between advocates of the view of the gradual path and advocates of the view of the non-gradual path. That is, is enlightenment a process of gradual development or is enlightenment attained instantaneously? The four grades are of course the attainments of stream winner, once-returner, non-returner, and arhant. This is an interesting problem and there are various allusions that bear on the topic that I hope to bring together into a coherent discussion in the future, which I am not prepared to discuss further today. It is, however, interesting that this path, the path of the arhant, which the Buddha doubtless taught, is not the path of the bodhisattva (lit. “wisdom-being”), which the Buddha himself followed, and the Pali Canon does make it clear that the ten powers of an arhant are not the same as and apparently inferior to the ten powers of a Buddha. An essential difference, moreover, is that a bodhisattva/Buddha is self-ordained by definition, as in the original samana tradition, which re-appears later in the Brahma Net and Srimala sutras, whereas an arhant always receives the dharma from a Buddha. The Buddha himself is also referred to as an arhant, but an arhant is never referred to as a Buddha. The distinction between an arhant and a Buddha became a point of contention following the Second Buddhist Council, which resulted in the great schism between the Mahasamghika majority, which subsequently developed into the Mahayana, and the Staviravada minority, which subsequently developed into the Hinayana, including the Theravada.

Sixth Recitation Section

Principle #34: The Dharma Retreat (6.1)

The imminent death of the Buddha obviously raised the problem of how the sangha should be organized after the Buddha’s death. In these passages, the Buddha addresses this issue. First and foremost, the Buddha states that the dharma and the discipline – the Dharma-Vinaya, which is the name the Buddha always gave to his teaching – is to be the teacher after his death. In addition, whereas during the Buddha’s lifetime the sangha was egalitarian, in which all members of the community addressed each other – even the Buddha – as “friend” (avuso), rather like the Quakers, after his death, the Buddha declared, the sangha should be organized as a decentralized hierarchy based on seniority, in which the junior monastics would address the senior monastics as “Lord” (bhante) or “Venerable Sir” (ayasma). Some scholars also hold that the formula of the Triple Jewel, i.e., the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, originated with Ashoka (3rd cent. BCE), whereas the original formula was singular. That is to say, the original Buddhists only took their refuge (more properly, “retreat”) in the Dharma alone.

Principle #35: The Minor Rules of the Vinaya (6.3)

Contrary to the fundamentalism that appears to affect many followers of the Vinaya today, the Buddha further declared that the “lesser and minor” rules of the Vinaya might be abolished. Unfortunately, when the Buddha said this, it did not occur to Ananda to ask the Buddha which of the rules were major and which were minor, so the First Buddhist Council led by Mahakassapa, the so-called Father of the Sangha, took the conservative approach of abolishing none of them. There are six Vinayas known today – that of the Theravada, Mahasamghika, Mahisasaka, Dharmaguptaka, Sarvativada, and Mulasarvastivada, three of which are still followed by the Theravada, East Asian Buddhists, and Tibetan Buddhists, but the scholarly consensus is that the Mahasamghika Vinaya is the oldest. The Mahasamghika subsequently developed into the Mahayana.

Although many religious Buddhists strongly emphasize the rules of the Vinaya, the original Buddhist sangha did not follow any fixed set of rules. These developed gradually over the course of the Buddha’s life in response to specific situations. Apparently, the Buddha was quite flexible about the observance of the rules. For example, according to the Vinaya itself the rules may be abrogated if required to do so for reasons of health or to prevent a crime. Alcohol and drugs were permitted for the purpose of healing. The Buddha frequently warns the monastics against attachment to rules, rituals, and beliefs. A Vajjian monk complained to the Buddha that he could not stand such training with so many rules and regulations. Far from reprimanding him, the Buddha then asked him whether he could stand the threefold training in higher morality, higher thought, and higher insight. In Mahayana, these became the three higher trainings. Once proficient in this, lust, malice and delusion would be abandoned and no wrong deed would be performed without needing to follow the rules as such. The implication, then, is that slavish adherence to the letter of the rules is not required to attain emancipation. Interestingly, the Vajjians also brought about the great schism in the Buddhist order during the Second Buddhist Council on this very question of rules.

The core of the Vinaya is given in the pattimokkha. When one analyzes these rules, one finds just about ten essential rules, very similar in fact to the bodhisattva precepts. You can find them in various places online including at http://en.dhammadana.org/sangha/vinaya/227.htm, grouped into rules that entail automatic expulsion from the sangha for life (parajikas), rules requiring an initial and subsequent meeting of the sangha (sanghadisesa) that result in a period of probation, indefinite rules (aniyata) based on acknowledgement of the offence, rules entailing confession with forfeiture (nissagiyyas), rules entailing confession (paccitiyya), violations that must be verbally acknowledged (patidesaniyas), and training rules (sekhiyavattas).

The Brahma Net Sutra (mid-5th century) is one of the oldest summaries of the bodhisattva precepts, which exist in many variations. The ten major bodhisattva precepts are:

- Not to kill or encourage others to kill.

- Not to steal or encourage others to steal.

- Not to engage in licentious acts or encourage others to do so.

- Not to use false words and speech, or encourage others to do so.

- Not to trade or sell alcoholic beverages or encourage others to do so.

- Not to broadcast the misdeeds or faults of the Buddhist assembly, nor encourage others to do so.

- Not to praise oneself and speak ill of others, or encourage others to do so.

- Not to be stingy, or encourage others to be so.

- Not to harbor anger or encourage others to be angry.

- Not to speak ill of the Buddha, the Dharma or the Sangha (lit. the Triple Jewel) or encourage others to do so.

In addition, there are 48 minor rules, which are not always regarded as mandatory. Note that the consumption of alcohol is not expressly forbidden, only trade. Mrs. Rhys Davids argues in the introduction to her translation of the Khuddaka-Patha that it is not the “sensible use” of liquors, but rather the habit, frequency, and occasions for indulging in them, that was originally prohibited (The Minor Anthologies of the Pali Canon (Oxford: Pali Text Society, 1996), p. xlvii). In any case, it is clear that the Vinaya regards it as a relatively minor offence, being #51 of the 92 pacittiyas, requiring confession only, preceded by “not to witness military activities” and followed by “not to tickle.” We know of course from the first sutta of the Digha Nikaya, the Supreme Net (Brahmajala Sutta), that the Buddha regarded ethical and moral rules to be oramattakaṃ sīlamattakaṃ – “merely profane (mundane), merely ethical (practices),” a statement that may surprise some religieux.

Principle #36: Earthbound Devas (6.11)

In a previous section of the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, we learned that at least some lower devas, the spiritual or celestial beings of light who occupy the higher planes of the 31 planes of existence, co-exist with human beings and influence them telepathically. The Buddha himself claimed to be aware of such devas and to have received teachings (dharma) from them. We know from our talk on the 31 planes of existence that at least three deva realms have intercourse with human beings, including the Four Great Kings, the Thirty-Three Gods, and the Brahma realms, and that the asuras (anti-gods) seem to occupy the same plane as humans, viz., the one world ocean. Here we encounter another interesting bit of lore with regard to the devas, for Ananda asks Anuruddha, a cousin of the Buddha and one of the five principal disciples, which devas he is aware of. Anuruddha was ranked as one of the foremost in the attainment of the divine eye (dibba-cakkhu). Anuruddha refers to sky devas whose minds are earth-bound and earth devas whose minds are earth bound in contrast to devas who are free from craving. The last category implies that devas are capable of practising dharma and of attainment, something that is implied throughout the Pali Canon despite the dogma that one often hears expressed that only human beings are capable of emancipation. I alluded to this question in a previous talk. The asuras of course are another example of earth-bound devas, having been cast down from the realm of the 33 Gods due to their association with samsara and the powers of nature. The earth devas refers to the Four Great Kings, the realm of what we refer to when we refer to the sprites, tree spirits, elves, fairies, pixies, gnomes, Japanese yokai, the Spanish and Latin-American duende, various Slavic fairies, and other similar beings of all times and climes. (See also Principle #28.)

Principle #37: Subhadda and the First Buddhist Council (6.20)

Subhadda was the last monastic to be ordained by the Buddha. Maurice Walshe states in a note that this Subhudda is not the same as that one, perhaps because this Subhadda, a barber, is stated to have ordained late in life, whereas the other Subhadda was a samana (wandering ascetic) of another sect. It is certainly a coincidence that two monastics with the same name were associated with the Buddha’s death and the period immediately afterward, but not impossible. On the other hand, some translations of the Mahaparinibbana Sutta refer to Subhadda the barber as “the late-received one,” referring perhaps to his being the last disciple to be personally ordained by the Buddha rather than to his age.[2] The Pali Canon denigrates him, and this may be the reason why he is distinguished from the samana Subhadda, but this may also reflect a sectarian prejudice. We know that the First Buddhist Council was contentious, and that this contentiousness persisted in later councils too. In any case, Subhadda the barber’s suggestion that the rules might be relaxed is what precipitated the First Buddhist Council.

The First Buddhist Council was called together shortly after the Buddha’s death by Mahakassapa, who was regarded as foremost in asceticism, despite the fact that Buddha said that the sangha should have no leader other than the dharma. Presumably, Mahakassapa also brought an ascetic orientation to the council and, as with all organizations, had both supporters and detractors. Indeed, it is clear from the Cullavagga that the council was sponsored by Mahakassapa’s group, and that others were excluded (see I.B. Horner, trans., The Book of Discipline (Vinaya-Pitaka) (London: Luzac, 1952; rpt. 1963), Vol. 5, p. 395, n.1). The First Buddhist Council was held during the rainy season three months after the Buddha’s death. Since the rainy season retreat begins in late June or July, it seems likely that the Buddha died in March, which is consistent with the statement that the sal trees between which the Buddha died bloomed prematurely. I have already talked about how the arhants at this council castigated Ananda for convincing the Buddha to ordain women and for failing to clarify which were the major and which were the minor rules of the Vinaya. Indeed, so deep was the misogyny of the arhants of this council that Ananda was castigated for allowing women to view the Buddha’s body after his death, which (they claimed) was defiled by their tears (op. cit., pp. 400f.). Presumably, Ananda too had his supporters and detractors, so we see here how the politics of the First Buddhist Council may have played out. It is an open question whether all the monastics present at the First Council were men. Dr. Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, in her article, “The History of the Bhikkuni Sangha” (http://www.thubtenchodron.org/BuddhistNunsMonasticLife/LifeAsAWesternBuddhistNun/the_history_of_the_bhikkhuni_sangha.html), argues that female monastics were also present.

If you are interested in learning more about the First Buddhist Council in the primary sources, you can read the 11th chapter of the Cullavagga in the Vinaya section of the Pali Canon here: https://archive.org/stream/p3sacredbooksofb20londuoft#page/392/mode/2up.

Note

1. Thus stated by most sources that I have consulted. Hajime Nakamura, however, states that the rainy season at that time was mid-May to mid-September (op. cit., p. 89). However, on the following page Nakamura identifies the beginning of rainy season with the fourth month of the Indian calendar. Unless Nakamura is using some other starting point unknown to me, this is the month of Asadha, which corresponds to June-July in the Gregorian calendar. Moreover, according to the Rasi and Rtu, May is still summer, monsoon season beginning in June-July. If Nakamura’s information is accurate, then we would have to place the Buddha’s parinirvana in February, corresponding to the transition from the pre-vernal to the vernal season. This is consistent with our hypothesis that the Buddha died in late winter.

2. Hajime Nakamura, however, identifies both Subhaddas as the same person: “Subhadda’s questions seem almost malicious. Later, after the Buddha’s death, it was Subhadda’s indiscreet words that led to the decision to hold the First Council” (trans. Gaynor Sekimiri, Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts, Vol. 2 (Tokyo: Kosei, 2005), p. 150).

Reference

Nakamura, Hajime (2005). Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts. Trans. Gaynor Sekimori. Vol. 2. Tokyo: Kosei. http://www.scribd.com/doc/105684143/Gotama-Buddha-Vol-2-Nakamura-Haijime-Trs-Sekimori-Gaynor-2005#scribd.